How would you define self-esteem? The Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “belief and confidence in your own ability and value.” No definition of self-esteem ever satisfied me because I cannot answer this simple question: Which one is the self, the one judging, or the one being judged? Where did the judging self come from anyway? Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki described the judging self as “extra.” “It is like having a head on top of the head,” he said. “You don’t need the extra head.”

I don’t believe the problem of “low self-esteem” is about judging oneself negatively. I think the real problem is the creation of a judging self. Allow me to contrast what it means to judge your value and abilities (the self) on the one hand, and your performance on the other. They’re not the same.

First, why would you question your value? Unless you believe that some people are born without value, how could you have no value? What does having no value look like? What is the value of questioning your value? I suppose my life may lose value when I’m breathing my last breaths, but I don’t think I will be too concerned about it then. I’ll get back to you on that!

What does it mean to “have confidence in your abilities” as some dictionaries define self-esteem. You may feel confident when observing a particular skill you have, but the action of recognizing an ability is observing. You may feel confident about one ability and be confident that you lack another. If you are aware of your abilities, and those you don’t possess, what is there to question? You can develop abilities, and you can accommodate for those you lack.

If you don’t read music, you can learn how. If you have a learning disability that makes it nearly impossible to learn how to read music, you can dedicate your time to another hobby, or do as my mom did and learn to play piano by ear. I can say that I’m confident in my knowledge of grammar. I’m equally confident that I have a poor memory and have learned not to rely on it. I rely on tools and strategies instead…and other people.

Evaluating performance is different from judging the self. It has a function. If you began music lessons last week, you are not going to play a recital this week, but you and your teacher will be evaluating your progress weekly. Evaluating progress helps you know how to allocate time for studying and practicing. You are not judging your value or your abilities when learning something new, you are simply observing progress in your skill development as you proceed from one lesson to the next.

Here is my suggestion for what to do about the judging self. The moment you notice that you are constructing a judging self, just observe that you’re doing it…without judgment…and say to yourself, “There’s that.” Say no more. Don’t say, “Oh, there is that damn judge again; why do I do that to myself?” That is judging. Acceptance of a tendency or an inclination is more informative and useful than self-criticism.

Saying “there’s that” allows you to simply notice the judging self. It prompts awareness that you are capable of dividing yourself into two selves. The bottom line is this: you can question your value and your abilities, or you can silence the judge.

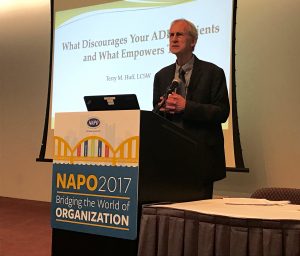

APO for allowing me to present my ideas about communication that can discourage ADHD clients and alternative communication that can empower them. I’m grateful also to members of the addnashville support group whose suggestions were incorporated into the presentation. We are helping many other adults with ADHD indirectly with the information shared with the organizers. I continue to be impressed with this profession, especially with the acceptance and sensitivity shown to persons with ADHD. Thank you NAPO organizers and members!

APO for allowing me to present my ideas about communication that can discourage ADHD clients and alternative communication that can empower them. I’m grateful also to members of the addnashville support group whose suggestions were incorporated into the presentation. We are helping many other adults with ADHD indirectly with the information shared with the organizers. I continue to be impressed with this profession, especially with the acceptance and sensitivity shown to persons with ADHD. Thank you NAPO organizers and members!