I saw “Maudie” this past weekend at the Belcourt Theater in Nashville. It was the best movie I’ve seen this year. Sally Hawkins’ performance as artist Maud Lewis was extraordinary.

In one scene, Everett (Ethan Hawke) wanted Maud to tell him who had thrown rocks at her as she walked down a country road to his house in Nova Scotia. Maud appeared undisturbed by the incident. She was accustomed to being taunted, having limped with arthritis since childhood. She was labeled a “cripple” by her family and people in the community. She told Everette that the rock throwers were only children. “Some people don’t like it when you’re different,” she said.

Indeed, some people don’t like difference. Spouses who once liked the excitement of dating someone with ADHD don’t like partnering with the difference in marriage. They often want the ADHD fixed…for them. I have heard many spouses say to their ADHD partners, “I’ve been in therapy fixing me; it is time you fixed yourself.”

Well, I wouldn’t mind having a “fix” for my ADHD, but I don’t expect to get one as an anniversary gift! And anyone who believes the ADHD difference is only a gift should tell me where I can exchange mine! I’m not that different from those troubled spouses; I like what is good about my ADHD brain and dislike what isn’t.

Being different from your spouse’s image of an ideal partner is not easy. But who is responsible for your partner’s choice to live with you, and for their response to your symptoms? Adults wishing to live well with ADHD can benefit from useful feedback that a partnership can offer, but also from not accepting sole responsibility for their partner’s happiness. The work of partnership is for both partners.

Some people don’t like it when you’re different. John Elder Robison knows that well. The title of his second book about autism is Be Different. Maud Lewis dared to be different and was abused for much of her life. She paid a price for her difference, but she thrived by creating…and her patrons paid a price for her art.

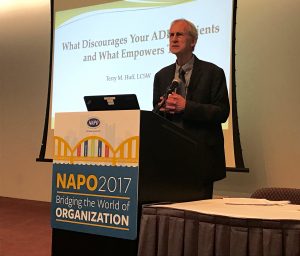

APO for allowing me to present my ideas about communication that can discourage ADHD clients and alternative communication that can empower them. I’m grateful also to members of the addnashville support group whose suggestions were incorporated into the presentation. We are helping many other adults with ADHD indirectly with the information shared with the organizers. I continue to be impressed with this profession, especially with the acceptance and sensitivity shown to persons with ADHD. Thank you NAPO organizers and members!

APO for allowing me to present my ideas about communication that can discourage ADHD clients and alternative communication that can empower them. I’m grateful also to members of the addnashville support group whose suggestions were incorporated into the presentation. We are helping many other adults with ADHD indirectly with the information shared with the organizers. I continue to be impressed with this profession, especially with the acceptance and sensitivity shown to persons with ADHD. Thank you NAPO organizers and members!